For more detailed historical information and citations, please refer to the Historic Resource Study: Island Legacies - A History of the Islands within Channel Islands National Park

While Santa Rosa Island had largely been stocked with sheep previous to 1901, cattle had been raised on the island in smaller numbers. Vail & Vickers managers chose to rid the island of sheep and slowly restock with cattle, giving time for the overgrazed vegetation to recover adequately in order to run a viable cattle operation. Vail & Vickers reached this goal by 1910.

Vail & Vickers traditionally raised Hereford cattle, first bringing herds from their Empire Ranch in Arizona, later buying young cattle from the Santa Cruz Island Company and all over the west. During the last years of ranch operation, they changed to a crossbreed that provided lighter beef as called for by modern tastes.

Vail & Vickers ran a stocker ranch, where calves were fattened on the ranch with island grasses and then sold directly to packing plants as "finished" cattle or, in later years as corn-fed beef became the standard, sold to feed lots for additional fattening. A stocker ranch differs from the common cow/calf operation in that cows were not bred to produce newborn calves to raise; they brought calves to the island for feeding, "stocking" the island with six-month-old calves.

Weaned calves destined for Santa Rosa Island arrived at Wilmington (1902-1939) near Los Angeles or Port Hueneme (1939-1998) in train carloads or by truck and were deposited into corrals at the harbor (occasionally in the early days they were shipped from Santa Barbara). Often the stock would be "stopped" at a mainland ranch where they would receive some or all preparation-branding, dehorning, vaccinating, and feeding. Stopping cattle allowed ranch owners to wait for the best island grass conditions. This preparation was also occasionally done on the island.

The cattle were marked with various brands. "V/V" didn't last long because it was graphically too complicated. After the war the managers used "VR" (Vail-Rogers), reflecting Ed Vail's partnership with Jimmy Rogers (son of the famous Will Rogers) on the Jalama Ranch near Lompoc. A heart-slash was the standard brand on the ranch for the last decade of the operation.

From the harborside corrals, vaqueros loaded the calves through chutes and ramps onto a vessel, either a barge, Vaquero, or Vaquero II. The vessels had pens aboard to regulate the number and weight of animals. Loading typically occurred in the dark. After a voyage of about five hours the livestock were unloaded onto the pier at Bechers Bay. After about three days in pens at the ranch house, where they would be fed and observed, calves were distributed to one of the six pastures on the island.

The total number of cattle depended on the weather, abundance of grass, and general range condition. During some dry years managers kept the ranch half stocked; the usual stocking level would reach about 6,000 to 7,000 head at the "spring peak." The largest number of cattle on the island at one time, consisting largely of calves, was about 9,000.

Vail & Vickers stocked the island using a double season strategy, where an overlap occurred between new calves and finished cattle that gave them two green seasons. From a new 300- to 450-pound calf arriving in the winter and early spring to a 750- to 1,000-pound feeder steer ready for shipping the following late spring and early summer, a steer spent roughly eighteen months on the island, gaining about 600 pounds.

While the herds could wander freely throughout the large pastures on the island, they tended to stay in groups in particular areas. The cowboys kept an eye on them but didn't interfere unless necessary, to doctor them or improve pasture utilization. Even at roundup time, the cowboys avoided roping cattle; instead they kept the cattle gentle by not "running ‘em." No supplementary feed was necessary. If the range conditions became poor, cattle were shipped off the island rather than import feed, which was expensive and labor intensive.

At roundup and shipping time the island came alive. The roundup followed a 100-year-old tradition of vaqueros tending cattle on horseback. The roundup, an icon of the romance of the West, is in reality a hard, dirty job that requires concentrated preparation, precise execution and judgment-and a good spell of rest when it is all over. The art of the roundup has been fully understood only by those who have participated in the activity. It requires a sure horseman or horsewoman on a good horse, possessing both agility and endurance; a knowledge of the land being worked, coupled with a good eye and a sense of how a steer thinks; and, perhaps most importantly, the ability to work as a team with little direct communication.

The island cowboys and their families spent three months in the spring on roundups around the island. Before the 1960s, cowboys gathered cattle to roundup grounds across the island mostly without the benefit of corrals. The eventual use of corrals throughout the island made roundups easier and faster and cut the number of cowboys needed. After being rounded up, the cattle were moved to smaller pastures close to the ranch in Bechers Bay and then eventually to the pens at the ranch, where they were carefully weighed in the scale house and assigned pens for shipment on the boat or barge.

During the Vail & Vickers years, a variety of vessels were used to ship the cattle to the mainland, including the Mildred E., Santa Rosa Island, Vaquero, Santa Cruz, barges and landing crafts, and, beginning in 1958, the Vaquero II. What follows is a ranger's account of the loading operation:

"The boat used for this unusual operation, the Vaquero II, is basically a shallow-drafted, floating cattle pen built especially for this purpose. The original Vaquero was pressed into service during World War II and never returned to Santa Rosa. The Vaquero II, a smaller boat, holds 100 head ... I watched the boat pull alongside the dock one morning. It was 4:00 am, dark and cold. An overhead light illuminated the end of the pier. Silhouettes of the cowboys could be seen against the morning sky. The voice of the foreman rose above the crashing of the waves on the beach.

When all was ready the overhead light was switched off then on, a signal to the cowboys to start the first group of 15 down the pier. Three vaqueros on horseback galloped behind the stampede. When the cattle reached the first planks of the pier they tried to stop, but the vaqueros cracked their whips and yelled, as their horses reared in the air. The herd was pushed reluctantly down the pier into a chute, forcing them to go single file. They were encouraged to keep moving with electric cattle prods or hot shots. Finally, each steer scrambles down the rusty ramp to the boat, where they were packed in so tightly they could not move.

As dawn broke, the Vaquero II, low in the water, began its journey, a journey it and the Vaquero before it had completed hundreds of times for more than 90 years. From Santa Rosa Island the Vaquero II lumbers the 55 miles to Port Hueneme where the cattle are sold at auction."

The sale price of a steer or cow was based on weight on the island at the time of shipping. Cattle lost some weight on the boat trip to the mainland and even more during shipping to feed lots. Vail & Vickers shipped cattle by rail in the early years and later by truck, to feed lots all over the West, including the Rocky Mountain states and the Midwest. Vail & Vickers owned a feedlot at Walnut, California, until around 1984. After 120-150 days of feeding on grains and supplements, the cattle were slaughtered and sent to markets as choice beef.

Cultural changes in the country after World War II helped raise public awareness of the importance and fragility of the resources on the Channel Islands. The booming post-war economy brought increased visitors and residents to California, especially to the scenic coastal areas, which saw greatly increased development. Events like the Santa Barbara oil spill and the discovery of the effects of DDT on seabird populations heightened environmental awareness and calls for protection of coastal resources.

On March 5, 1980, President Jimmy Carter designated the Channel Islands National Monument islands of Anacapa and Santa Barbara as a national park and added Santa Cruz, San Miguel, and Santa Rosa Islands.

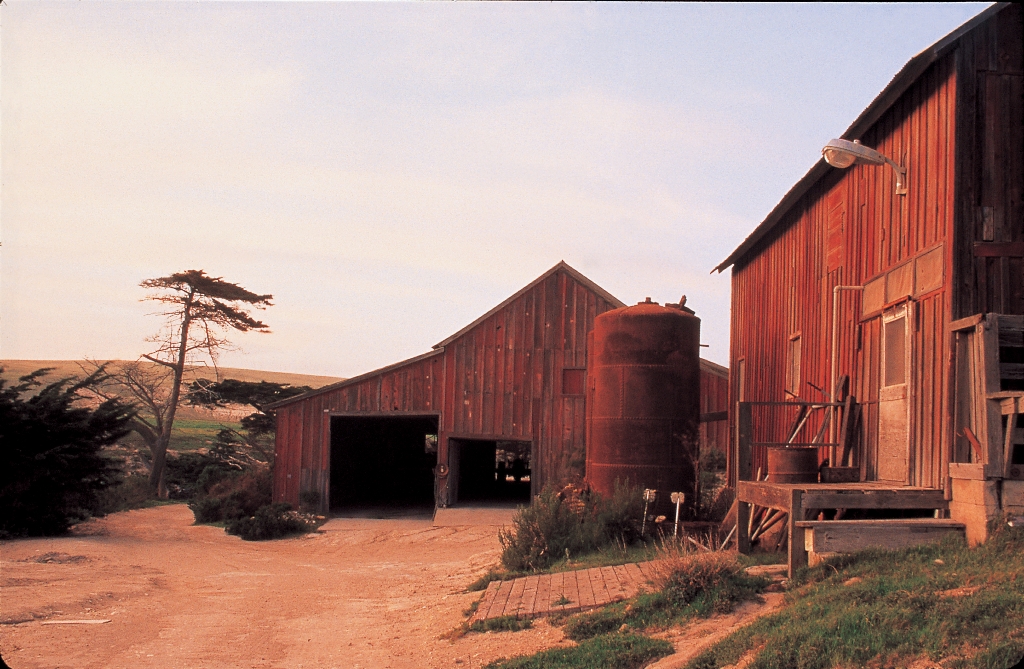

In 1986 the National Park Service acquired Santa Rosa Island from Vail & Vickers for nearly $30 million. The ranching operation continued until 1998 when the final roundup brought a close to the last working island cattle ranch in the continental United States and an end to a truly unique way of life.

For almost a century, Vail & Vickers operated one of the largest and most productive beef cattle ranches in California. Four generations of family members acted as stewards of the land managing the ranch in the traditional system of vaqueros (Spanish for "cowboys"), tending cattle on horseback, and preserving the last intact large Mexican land grant rancho in California. Their commitment to ranching traditions preserved an undeveloped, historic landscape that greatly contributed to Santa Rosa Island's inclusion in Channel Islands National Park.

Cowboy Life

The life of a cowboy, as personified in tales of the old west, had perhaps its ideal venue on Santa Rosa Island. Although without a saloon to saunter down to in the evening and lacking in shoot-outs, island cowboys were isolated from mainland progress and hence hung on to a passing way of life for a few extra decades. Once left at the Bechers Bay pier, the cowboy did almost nothing but be a cowboy, day and night. Life revolved around the bunkhouse, tack room, and range, as the men herded cattle, fixed fences and cared for their tack and horses.

Al Vail, for 25 years a cowboy then 36 more as ranch manager, described the life of a Vail & Vickers employee: "A cowboy does a little o' everything. You know, the reason for the island is to run cattle . . . in between when we're shipping cattle there's lots of other work, like fence building, breaking colts, do anything that comes along as far as maintaining a ranch."

Vail & Vickers needed six or seven men to handle the day-to-day ranch duties and, before building corrals around the island in the 1950s and 1960s, required even more for roundups. Most cowboys tended to be happy with the island life, and the managers were lucky to have steady crews, especially in the 1930s and 1940s. Vail spoke on the hiring practices at the ranch:

"Most of the personnel we have we get through word of mouth . . . We never had any luck going through an appointment agency . . . If the guy's a good cowpuncher and he says his friend is a good cowpuncher then you hire him."

Many cowboys followed the Vail family from their ranch in Arizona to Santa Rosa Island in the years after the island was purchased. One of the most storied of the old Arizona cowboys was Juan Ayon, who spent over 50 years chasing cattle, building fences, cooking, and keeping gardens on the island. Ayon was born in 1887 in Mexico and worked at the Empire Ranch for many years, forming a bond with the Vail family that lasted three generations. He is thought to have arrived at Santa Rosa Island around 1911. It has been written that:

"Juan, who was heavy-set with a short, stocky build, had great physical strength, and possessed many talents. He was not only an experienced cowboy, but also a good ranch hand as well-he milked cows, built fences, broke horses, nurtured the island's garden, and occasionally worked as the island cook (he always gave that assignment a fight and often ended up cooking only for himself!). Apparently his reputation of having a curmudgeon-like personality combined with a slightly humorous nature was well-deserved."

Many of the cowboys, like Jesus Bracamontes, came from Mexico. Jesus was born in January 1925 in Sonora, Mexico, and spent his whole life as a cowboy in Mexico and the United States; he worked for more than 35 years on Santa Rosa Island. During WWII the Vails enrolled in the Bracero Program, created by the Farm Security Administration and the Mexican government to help staff agricultural operations at a time when labor was short. The program granted temporary visas to 2.6 million Mexican citizens and helped find them work in the United States.

Cowboys worked seven days a week, sunrise to sunset. They were allowed four days paid leave on the mainland every six to eight weeks, or every month if not working cattle (vaqueros were also given longer vacations to go home to Mexico). It was an isolated life, where you couldn't run to town when you wanted. Office manager Tom Thornton took care of supplies for the cowboys:

"They'd send us a shopping list or call over after the phone became a very common and very easy thing to use. A simple matter. They would hope that [the clothes] fit. They always buy their shoes large so they can get thick socks or thinner socks. Buy their leather to make their chaps and to make saddles and buy their rope for their lassoes etc. You are dealing with a real family over there. "

The risks of isolation, of getting injured or seriously ill out on the island, didn't seem to bother many of the cowboys. Bill Wallace, who was hired in 1948 and was ranch foreman from 1968 to 1999, probably put it best when he said, "I've been out here just about fifty years. Well, once you get out here, it's damned hard to find a reason to ever go back. I only go into town when I absolutely have to. That's about once or twice a year. And that's too [expletive deleted] much."

Tom Thornton speculated on why Vail & Vickers was so successful in getting and keeping good cowpunchers on the ranch:

"[T]he Vail & Vickers cowboys are probably the best fed cowboys in the world. They get what they want. Al has no restrictions on . . . reasonable foods. So they eat very well. Probably that's one reason they stay so long. They are probably the best paid cowboys in the country. There is nothing "pickey-unish" about Santa Rosa people."

anta Rosa Island provided a unique backdrop for ranch life. While it was not the life for everyone, many of the cowboys and foremen stayed on for much of their working lives, dedicated to the island traditions and their employers. Those traditions contributed to the preservation of the "old ways" on Santa Rosa Island, a place almost untouched by the hurry of city life and pressures of development from nearby suburbs. The end of ranching in 1998 brought to a close a truly unique way of life in coastal California.

Horses

Santa Rosa Island's herds of horses served many purposes. Foremost, they worked at the most critical times of ranch operation: roundups and moving cattle. They also provided transportation, labor, and recreation for visitors and family.

Ranch managers kept about forty head of riding horses as well as twelve to fifteen brood mares. Additional horses, including yearlings, resting, and retired horses, brought the number to well over a hundred. The horses, mainly quarter horses, were bred and raised for ranch use. Known around southern California as a fine herd of cattle horses, each was trained by the cowboys and foremen to perform the jobs unique to the island.

Diego Cuevas spoke of the ranch philosophy on horses:

"Important part of the island was the horses, was number one . . . you gotta learn from the horses, teach ‘em to lead, got to teach ‘em so you can walk to and touch and play with their feet and make them gentle. That's one of the most important parts. So you have the job, the cowboy gotta do all those things like that. You know, train the horses from beginning from baby to three or four years old. So you can drive it and then you start teaching it how to respond to the reins. Once you do that you start teaching it how to work cows. And you try your best to make a good gentle horse at the same time. Working horse and gentle horse. Lot of the horses they see that they begin to get to be gentle and nice, you can play with them and they make good kid horses, because on the island you always have somebody that never ride a horse and then you can put him on the horse and you can trust him."

A cowboy would be assigned five or six horses to ride and care for. Usually he would break his own horses, train them, and use them exclusively during roundups.

Working island horses spent their time in the House Field, roughly 640 acres west of the ranch complex. Yearling and older horses were turned out onto the Soledad and Green Canyon Flats. Ranch workers sowed oat fields in the flat areas east and south of the ranch house to produce feed for the horses; ranch workers cut and baled oat hay in May, weather permitting.

Earlier in the century, horses performed most of the transport labor, hauling wagons of materials to various parts of the island. The first ranch vehicle, a Fordson tractor, arrived in 1939, and island managers started to use trucks in the 1950s, but horses remained the favored mode of transportation. The Vail children and their friends looked forward to island visits, which afforded the freedom of riding horseback in the hills, searching out pigs, and having picnics in favorite spots.

Hunting Pigs, Deer, and Elk

Hunting had a long tradition on Santa Rosa Island, with the earliest reference dating back to 1853. Nonnative pigs, deer, and elk were all privately and commercially hunted on the island.

Pigs

The origin of pigs on the island has not been determined, although it is known that sometime after 1844 Alpheus Thompson raised "a lot of hogs." Since then, pigs had become a source of delight to the hunter and a bother to the rancher. Charles Holder wrote in 1910 that "years ago wild pigs were placed on the island and are now ‘wild hogs' . . . dangerous to approach or hunt on foot." Al Vail stated that hogs inhabited the island long before Vail & Vickers took possession of the island in late 1901. In the early 1930s, according to Vail, they traded hogs for Catalina Island quail, shipping them over on the Vaquero.

Arthur Sanger, who hunted hogs on the island between 1910 and 1917, described "wild hogs weighing as much as 150 and 200 lbs. with curved tusks six inches long. They have the appearance of large hyenas, high heavy shoulders and low rumps." He continued, "Many times they charged us with their teeth snapping with a grinding noise as if they wanted us to know what to expect if they reached us, but they never did. At the time I will admit that I felt more like running than shooting. We had some exciting experiences and we learned that if you corner or wound a tusker, he will always charge you."

Not only was pig hunting a popular sport on the island, it also became a necessary means to keep the population in check and slow the damage caused by their voracious rooting. Vail claimed that the hogs ate the cattle's molasses blocks and dug up valuable soil, which caused erosion, encouraged weeds, and reduced pasture productivity.

The NPS decided to eliminate the feral pigs, citing soil disturbance and the nonnative status of the approximately 500 to 4,000 animals (the population varied wildly depending on island conditions). The 1984 supplement to the General Management Plan noted that feral pigs, not to mention livestock, elk, and deer, would be removed from Santa Rosa Island. A major eradication effort in 1991 and 1992 eliminated all pigs from the island.

Elk and Deer

The elk and deer herds originated with the desire of the ranch owners to make the island "a sportsman's paradise." Walter Vail's sons, N. R., Mahlon, and Ed were ranchers and businessmen and worked to import elk and deer as a source of income and for their pleasure and that of visitors.

The first record of elk on the island came from a writer that visited the island in 1892 and reported on an ill-tempered pet female elk that "weighed as much as an ordinary horse." N. R. Vail wrote that around 1905 they obtained three elk from Oregon and a few years later a bull. One story goes that around 1908 an old elk that had been the mascot for the Elks Club in Long Beach was retired and taken to the island. Other family members recalled that the elk were imported in the 1910s. In 1911 a local newspaper reported on a herd of nine elk on Santa Rosa Island, stating, "it is an ideal range for them, and the day may come when the island may be well stocked with this species of game, now becoming extinct in other portions of the continent. Absolute protection is guaranteed them on the island." By 1994, the elk population had grown to approximately 900.

Margaret Vail Woolley said that the elk "were brought over with the idea that someday they'd be hunted, or at least they'd be meat producers and be profitable." Difficulty in getting fresh meat to shore, the depression, and refrigeration problems hindered those plans, and the elk were hunted only sporadically.

Family members and friends of the Vails and the Vickers enjoyed elk hunting. In the 1950s, under Ed Vail, a number of prominent men came to the island to hunt not only elk but also deer and pigs, including Governor (and later Chief Justice of the Supreme Court) Earl Warren, Bing Crosby (who had a ranch in Nevada and sold cattle to the Vails), and newspaper publisher and More descendant Thomas Storke.

Deer have been reported on Santa Rosa Island as early as 1880. The Vails brought deer over from Arizona's Kaibab National Forest in 1929-30. By 1994, the deer population had grown to approximately 1,000.

The Vail family began hosting commercial hunts for elk, deer, and pigs as early as 1979. Multiple Use Managers Inc. was hired to help manage the herds and to operate the commercial hunts. This business relationship lasted for the entire 32 year run of the commercial hunting program on Santa Rosa Island.

The federal government purchased the island in 1986 and Vail & Vickers retained a 25 year right to use and occupy most of the ranch complex at Bechers Bay. The NPS also permitted the hunting operation for that period. The deer and elk were eliminated in 2011.

Is there something we missed for this itinerary?

Itineraries across USA