Preserving the Past

An island ranch is a study in self-reliance. With no stores, phones...everything has to be fashioned from whatever is on hand; it's the art of making do.

-Gretel Ehrlich, Cowboy Island: Farewell to a Ranching Legacy

While the isolated island offered ranchers several advantages over the mainland, including no predators and the world's best fence (the ocean), it created special challenges as well. Supplying such a remote outpost was probably the most considerable of these. The transportation of supplies and stock on and off the island was always an adventure-the distance to the mainland, rough seas, and high expense made it very difficult.

However, ranchers adapted to the challenges of island life through self-reliance and, as one ranch foreman wrote, "learning to make do with what [they] had." In order to produce income and be as self-sufficient as possible, ranchers developed a diverse operation: they raised barley and potatoes, maintained a vegetable garden, and imported different animals, including sheep, cattle, horses, mules, pigs, chickens, turkeys, and ducks.

Not all of these enterprises succeeded. Several attempts to grow crops were severely hampered by the island's unrelenting winds and blowing sand. And droughts caused ranchers to remove their livestock, impacting the raising of wool and meat for market.

Nevertheless, ranching persisted for over 100 years on San Miguel Island and included such colorful characters as George Nidever, a prominent California pioneer, William G. Waters, an eccentric entrepreneur, and the well-publicized family of Herbert Lester.

Nidever was the first to begin ranching in earnest on the island. In 1850 he brought 45 head of sheep, 17 head of cattle, two hogs, and seven horses and by 1862 the stock had increased to 6,000 sheep, 200 head of cattle, 100 hogs and 32 horses. During the drought in 1863 and 1864 Nidever lost most of his livestock and those that remained denuded much of the island, leaving just sand dunes and drifts.

Nidever is most noted for finding the "Lone Woman of San Nicolas Island." She was an American Indian woman lived isolated on the remote island for 18 years after her people went to the mainland in 1835. Eighteen years later, Nidever, while collecting seagull eggs on the island, found her and eventually brought her back to Santa Barbara where she delighted the town with her language, songs, and dance. Tragically, however, within a short period of time she became ill and died.

In the 1880s William Waters acquired the ranching rights to the island and became the longest-lived resident of the island, spending almost thirty years there. He proclaimed himself the "King of San Miguel," stating that the United States had no right to the island and that it was his for the taking. When the government tried to investigate, Waters threatened to shoot any invaders of his nation. According to Waters, only when Grover Cleveland sent a civil request as the head of one nation made to another would he allow government surveyors to access to the island. In reality, what probably convinced Waters to allow the survey party access was the visit to the island by a U.S. Marshal and a contingent of armed men. Waters was eventually denied his request to remain as the self-appointed king and remained a U.S. citizen until his death.

Waters and his work staff constructed the island's first road from Cuyler Harbor beach to the top of the island via Nidever Canyon, blasting rocks and making a fine but narrow grade for hauling supplies up and products down. The road remains as a hiking trail today and some of the rockwork is still evident.

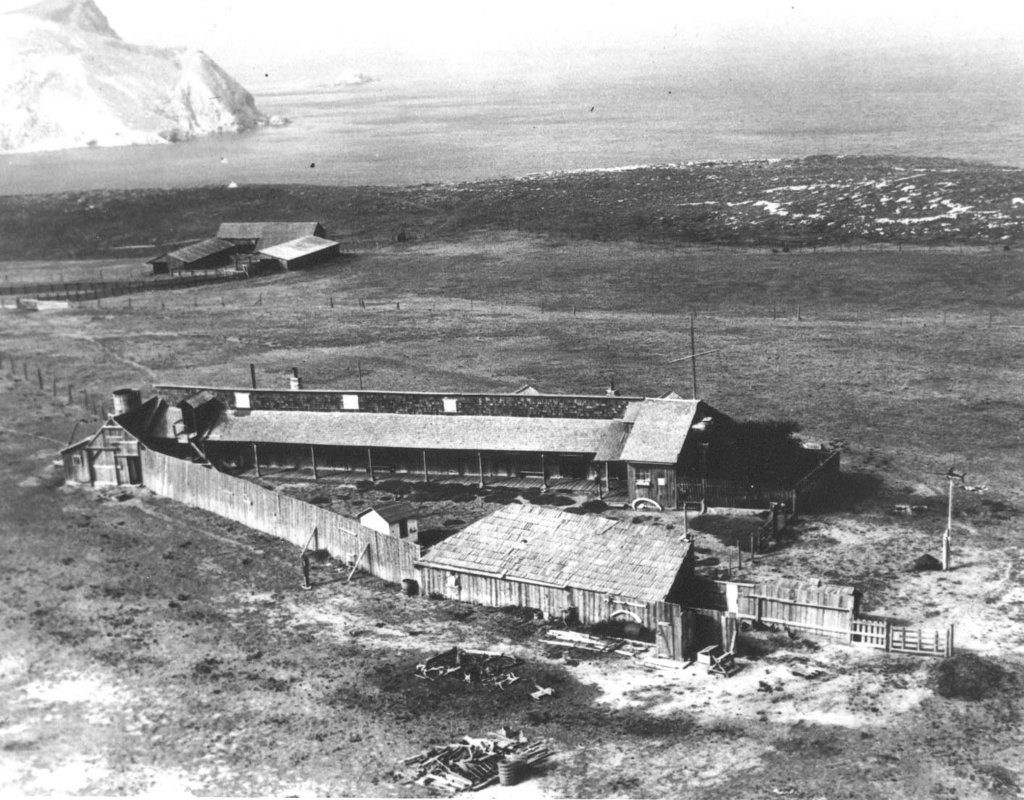

Waters and his staff also constructed the island's largest ranch house-the ruins of which lie before you. After sand drifts had buried the old ranch house in upper Nidever Canyon, work began on this new house in 1906. It was constructed out of materials salvaged from shipwrecks around the island - most of it from the lumber schooner the J.M. Coleman which had gone aground inside Point Bennett in 1905. The house was 125 feet long and 16 feet wide with double-walls to withstand the strong winds. A blacksmith shop/harness room, tool shed, well, cistern, and root cellar were also constructed.

Robert Brooks acquired the island lease from Waters in 1917 and hired his friend from the Army, Herbert Lester, to manage the ranch from 1929-1942. Herbert brought his new bride, Elizabeth, with him to the island, and eventually had two daughters out here, Betsy and Marianne. Herbert and his family enjoyed isolated island life and saw it as an escape "from the shallowness of civilization and its incessant and inconsequential demands."

San Miguel Island soon came to be known as Lester's Island, and following in Waters' footsteps, he too dubbed himself the "King of San Miguel." He wore a makeshift insignia to designate his rank and their mailbag read "Kingdom of San Miguel."

Numerous stories are known from the Lester era, due to extensive coverage in the press. In 1940, Life magazine ran an article about the family entitled "Swiss Family Lester," including a story about the kids being educated in the "tiniest schoolhouse in the world."

In 1937, The Santa Barbara News-Press carried an article headlined, "Man's Life Saved by Island King." The story described how Robert Brooks was working on the reconstruction of the landing down in Cuyler Harbor when he lost his footing, fell and impaled his thigh on a rusted bolt. He was in danger of bleeding to death if he did not receive immediate attention. Lester, relying on his Army experience, quickly sterilized the wound with Lysol and stitched it closed with a curved burlap sack needle and some fishing line. The ranch had no radio at the time so the American flag was hoisted upside down in the hope of attracting a passing vessel. Two weeks later their regular supply ship arrived and transported Brooks to the hospital. The doctors were quite impressed with Lester's work and refused to take any pay as Lester had completed all the treatment necessary and had saved Brooks' life.

In 1948 island ranching came to an end when the Navy revoked Brooks' lease so that the island could be used as bombing range to train and test for the nation's Cold War defense system.

Unfortunately, the ranch house built by Waters and lived in by the Lesters burned down in 1967 when the Navy inadvertently started a fire during weapons testing. All that remains today is what you see before you (piles of rubble, hardware and metal pieces, and two cement-lined excavations considered to be a cistern and a root cellar) and, of course, the stories of survival on a weather-beaten and most isolated island.

Even today, the isolation of this island still affects visitors and the National Park Service. Public boat trips for park visitors are limited to only a few days each month during the summer and visitors must bring (and carry up to the top of the island) all their own food and water. Park staff must import food and drinking water as well, and have established a solar power system for energy. Like so many who visited and resided here before, we must learn to make do with what we have.

For more information on ranching history, visit Lester Ranch.

Is there something we missed for this itinerary?

Itineraries across USA