Lester Ranch Site

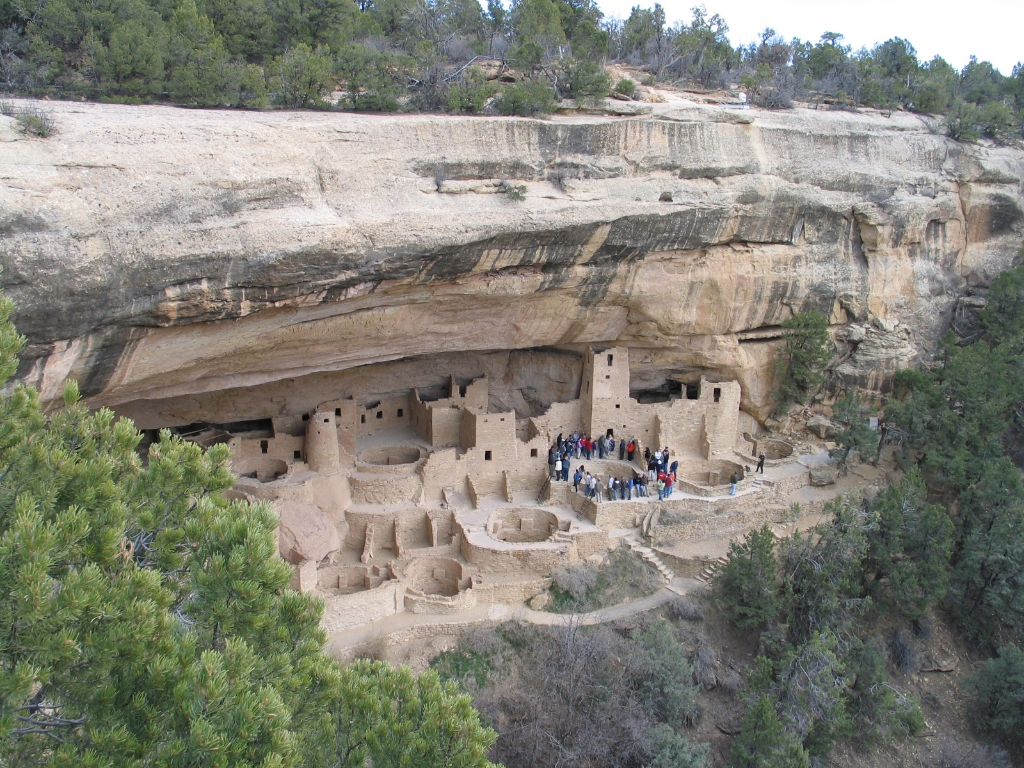

Before you are the ruins of the island's largest ranch house. Work began on this new house in 1906. It was constructed out of materials salvaged from shipwrecks around the island - most of it from the lumber schooner the J.M. Coleman which had gone aground inside Point Bennett in 1905. The house was 125 feet long and 16 feet wide with double-walls to withstand the strong winds. A blacksmith shop/harness room, tool shed, well, cistern, and root cellar were also constructed.

Unfortunately, the ranch house burned down in 1967 when the Navy inadvertently started a fire during weapons testing. All that remains today is what you see before you-piles of rubble, hardware and metal pieces, two cement-lined excavations considered to be a cistern and a root cellar, collapsed chimney and fireplace, and the remains of a fig tree.

Island Ranching History

For a summary of ranching history on the island, please see the guided tour stop 5. What follows is a detailed account of ranching history on San Miguel Island.

Sheep ranchers occupied San Miguel Island for almost 100 years. Little is known about the first, a person named Bruce, but the succession of settlers to follow included George Nidever, a prominent California pioneer, William G. Waters, an eccentric entrepreneur, and the well-publicized family of Herbert Lester, whose isolated existence was made charming by Lester's personality and the perseverance of his wife and young daughters. Lester's life on the island ended tragically, but his family's story is one of the more interesting in the history of the California coast.

George Nidever's Sheep Ranch, 1850-1870

It is not known when sheep first grazed on the island but reports indicate a date prior to 1850. The only source of information regarding mid-century grazing is the narrative dictated at 76 years of age by California pioneer George Nidever, the mountain man and trapper who settled on San Miguel Island in 1850. Nidever bought a schooner in San Francisco in early 1850 and soon "bought out the interest of a man by the name of Bruce" who had been grazing sheep on San Miguel Island.

Nidever imported 45 head of sheep, 17 head of cattle, two hogs and seven horses and by 1862 the stock had increased to 6,000 sheep, 200 head of cattle, 100 hogs and 32 horses. During the severe drought in 1863 and 1864 Nidever lost most of his livestock ("5,000 sheep, 180 cattle, a few hogs, and 30 horses"). The later Nidever period on the island marked the beginning of the destruction of the rich native flora on the island, as Nidever's sheep denuded much of the island, leaving just sand dunes and drifts. Only eight years after leaving the island, Nidever related that he had been told that the island "is almost covered with sand."

Nidever and his sons occupied an adobe house located in an arroyo up from Cuyler Harbor in the west tributary of what has been called Nidever Canyon.

Nidever took his schooner over to San Nicolas to hunt for sea gull eggs in April of 1852 and discovered the footprints of an old Indian woman who had been left on the island when the rest of the Indians were removed. In July of 1853 he returned there and "rescued" the woman. Nidever took the "lost woman" of San Nicolas to his Santa Barbara home where his wife cared for her until she soon died.

The Heyday of Sheep Ranching

The mysterious Bruce and then the Nidever family established sheep ranching on the island, but it was their successors who transformed it into an industry, albeit on a small scale. Although minor in scope, sheep ranching brought the first Euro-American settlers to the island and was the most significant and long-lasting historical use. The subsequent destruction of the island's vegetation by sheep would have far-reaching ramifications, not only in limiting the success of ranching but in paving the way for preservation and restoration by government agencies of the 20th century.

Following Nidever, the Mills brothers and their Pacific Wool Growing Company grazed their sheep on the island's grasses and packed wool for sale to mainland markets for 17 years. William G. Waters and his sheep then occupied the island for almost 30 years, during which the federal government affirmed its ownership of San Miguel Island. Robert Brooks held a government lease for another 30 years but did not reside there; he installed Herbert Lester, an intelligent and colorful man who raised a family on the isolated island and garnered a great deal of national publicity in the process. Lester's occupation ended in tragedy, and soon sheep ranching gave way to occupation by the United States Navy and a new era in island history. Sheep ranching dominated the history of San Miguel Island and, while not a major contributor to the state's agricultural economy, is made significant more by its protagonists, the Nidevers, Mills', Waters' and Lesters, whose stories are told below.

Mills Brothers Ranch, 1870-1887

The Mills brothers, Hiram and Warren, operated a sheep ranch on San Miguel Island for the same number of years as Nidever had, and continued to contribute to the destruction of the island's flora. They and their partners formed a business called Pacific Wool Growing Company and built an undetermined number of wood frame buildings in the canyon above Cuyler Harbor. Theirs was the first organized business enterprise on the island.

Hiram Mills purchased an undivided half of the island on May 8, 1869 from the Nidevers for $5,000, and then bought the rest on April 26 of the following year for $10,000, including the livestock, personal property and improvements. Mills and his partners called their enterprise the Pacific Wool Growing Company and had an office in San Francisco. Mills has been credited with building a two-story frame house in the canyon east of Nidever's adobe but apparently visited the island only occasionally. After surviving the collapse of the wool market in 1876 the Pacific Wool Growing Company continued in business, likely with caretakers on the island living in the house. Other activities, including otter and seal hunting and abalone harvesting, were pursued on the island during those years.

Visitors to the island in the 1870s described a sheep operation out of control as the animals grazed the vegetation down to the sand. In 1874 William Dall of the Coast Survey visited the island and wrote, ". . . there are no young trees . . . as the omnipresent sheep crop every green thing within their reach to the ground." Coast Survey employee and archeologist Paul Schumacher spent four days on the island and later wrote of starving sheep, calling the island "a barren lump of sand." Wheeler noted drifting sand in 1879 as he described the island as barren and extremely desolate.

William G. Waters at San Miguel Island, 1887-1916

In November of 1887 Captain William G. Waters bought a half interest in the island and the livestock that were on it for $10,000 from Mills. As of January 1888 the ranch supported 4,000 sheep, 30 head of cows and horses, an undisclosed number of pigs, turkeys, chickens, one dog and two cats. Waters would be the longest-lived resident of the island, spending almost thirty years there. Waters continued the day-to-day business of sheep ranching, but added flavor to the island lore with stories of his eccentricities and fondness for publicity.

Mrs. Waters' carefully kept diary described the island as a productive farm. For example, in January 1888, the men commenced to harrow at least two fields and in February planted 47 acres in barley. In the winter during which she wrote, rain was plentiful, filling the rain barrels and evidently bringing forth good crops all around, as she wrote of following her husband to the grain fields in the spring and of the two of them cutting and stacking the hay, at one point in a pile 30 feet high. During the winter and spring Waters bought a mowing machine and a reaper for the barley hay. Waters had a barn for grain at "the top of the hill" and built a tool house in January. They grew their own vegetables, had a fenced potato patch in the sand above the house, built a grape arbor, and churned butter. Dairy products, poultry, eggs and pigs were abundant although they did depend upon the supply boat for flour and fruit.

William Waters and his hired hands worked hard six days a week. The men built a road from the beach at the harbor to the top of the island, blasting rocks and making a fine but narrow grade for hauling supplies up and products down. The road remains as a hiking trail today, and some of the men's rockwork is evident.

They also maintained a boathouse at Cuyler Harbor by regularly salvaging lumber off the island's beaches. The ranch was equipped with a forge, as Mrs. Waters wrote of Jimmie making irons for the cart. The family traveled to the west end for good water, considering the water in the canyon to be unpalatable.

Waters hired sheep shearers on the mainland every spring, who worked in the shearing sheds and bunked in the ranch house. In a traditional practice, a shearer would be given a ficha, a punched, metal token marked "San Miguel Island" and on the other side "W. G. Waters / one sheep" for each sheep shorn which he would trade in for payment at the end of the day or shearing period. According to later reports, a ewe brought a nickel and a ram a dime.

By 1889 Waters had been cultivating parts of the island. Documents showed that he owned hay farming implements that year, and the following year, when Waters took sole possession, the island supported 3,000 sheep, 150 cattle, ten horses and mules, as well as hogs, goats and poultry. Waters owned wagons, carts, plows, harrows and mowing machines. A map of the island made by C. D. Voy around 1893 depicted cultivated fields on the mesa lands above Cuyler Harbor.

During Waters' term on the island a geological event changed the topography of the island and its surrounding waters. Observers noted that sand beaches were increasing in size and number in the 1890s, and the Coast Survey reported great sand dunes spilling into Cuyler Harbor from the west, causing the destruction of the large kelp bed in the harbor noted by Forney in 1871. Then in March of 1895, a huge landslide occurred, as reported by Waters in the San Francisco Examiner shortly after the event:

"There has been quite a commotion over here. The land that formed those high bluffs back of the boathouse has sunk more than sixty feet perpendicularly and forced itself into the harbor, raising the beach and rocks which have lain at the water's edge for thirty years some thirty feet above. This upheaval extends up and down the beach more than 1,000 feet. The boathouse is in a depression, and the sand and stones in front of it are over thirty feet high. This must have happened Saturday, March 8th. I felt a shock, but as the wind was blowing strong thought nothing of it. It must have come very suddenly, as lots of fish and small crabs were caught in the upheaval and left high and dry out of the water.

The extent of this upheaval covers over twenty acres, and as it is continually on the move I cannot tell what the next change will be. Whether this extends far under the water in the harbor I do not know. It will leave huge stones on the west side of the harbor and change the landing. My boats and those of Captain Ellis are all right. The land was raised in the boathouse, while the posts remained as they were.

It is a strange and peculiar upheaval. Some scientific man should see it. I give it up. I shall be obliged to remove my corral to the other side of the spring and rocks. The boathouse is now about 300 feet inland. Captain Dally will tell you all about it. I went all over it, but as it was on the move I thought I had better return to solid land and await events."

Waters found the boathouse pointing north/northeast instead of east, with a bluff between it and the water about 100 yards wide and 60 to 70 feet high. The movement at Cuyler Harbor, considered by modern geologists as a large rotational slump-landslide, obliterated the many tide-level caves in the southwest harbor and caused the U. S. Coast & Geodetic Survey to re-survey Cuyler Harbor that November and produce a new chart of the harbor reflecting the significant changes in the harbor bottom and the land topography.

The following year, 1896, brought conflict between Waters and government surveyors. Newspapers had earlier reported that, since San Miguel Island had not been mentioned in the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, it was not a United States possession and thus could be used by England as a coaling station. The government determined to investigate and assembled a party of surveyors to map the island. Considering the island to be his, Waters would have none of it and threatened to shoot the invaders. U. S. Marshal Nicholas A. Covarrubias then put together a party of 22 men, composed of the surveyors and a contingent of armed men, and armed himself with orders from President Grover Cleveland to admit the survey party. Covarrubias and his contingent left Santa Barbara on July 7, 1896. According to a newspaper account, Waters met the marshal on the beach, protested the entry, but did not resist the order when shown it. He stipulated that the party could not kill his sheep, but that Waters himself would provide meat for the party and transport of their equipment and provisions. In an interview made more than 25 years later, Covarrubias had a different view of the events. He said that he had "set about recruiting an army, chartered a vessel and rounded up a formidable bunch of deputies, armed them to the teeth, and set sail for the island. When Waters saw them in the offing, he decided that the Army was much too strong, and he surrendered at discretion. He was invited aboard and proved his friendship by eating prodigiously of the good things which had been secured for the Army."

Whatever the true story of the landing, apparently all went smoothly with the survey, and the party returned to the mainland days later without incident. Waters did, however, file a protest that was placed on file at the Surveyor General's Office in Washington.

Sand drifts reportedly covered Waters' old ranch house in upper Nidever Canyon around 1906. Around that year under Waters' guidance, resident manager John Russell built a new ranch house out of salvaged wood from shipwrecks and cargoes of lumber schooners that had come to grief on San Miguel Island. For example, the J M Colman had gone aground in 1905 just inside Point Bennett; Russell hauled the redwood lumber it carried up from the ship to the ranch house site with Mexican burros. The house was 125 feet long, 16 feet wide, and double-walled to withstand the winds that blew almost perpetually and reached velocities up to 100 miles an hour. Later another leaseholder, Robert Brooks, and Russell built a fence erected at an angle to the westerly wind to shield the house from wind and sand. As lumber drifted ashore from shipwrecks (for instance, the Comet), the house was rebuilt, fences and outbuildings repaired. Waters and Russell also constructed a blacksmith shop/harness room and a tool shed, and a new well, cistern and root cellar.

Waters and Russell used tongue-in-groove hardwood for the interior finish of the house and designed the north side so that it could resist the northwest winds, although portholes afforded a view of the mainland. One historian surmised that the men built the house one room at a time as materials became available. The house had an interesting roofline, being a long shed with a gabled room on the east end and a hipped-roof room addition on the other. A long porch ran the length of the interior courtyard and numerous windows and doors opened on this courtyard. Two dormer windows on the roof slope faced the Channel and mainland. The house contained eleven rooms, with another added at an unknown time. From east to west the rooms were: a bathroom; a bedroom with anteroom and small closet; a dining room; three small bedrooms, reportedly used at times for shearers during the season; a serving room; a kitchen with a chimney, pantry and closet; a storage room; a small room with a closet; a laundry room with a meat cooler; and an added hallway or entranceway with a revolving door.

A Santa Barbara newspaper noted the improvements: "Recently Mr. Waters has erected a fine eight-room house on the island. The building has running water in every room and compares favorably with any city dwelling in the number and quantity of its modern conveniences. There is also a fine sheep shearing shed on the island."

On November 18, 1908, a clipping from the San Francisco Call, date-line Santa Barbara, related that title to the whole of San Miguel Island was at stake in a suit coming up the following day in Los Angeles. The case, it read, had been pending for four years. The island, it claimed, was transferred from Elias Beckman to W. G. Waters in 1892. Beckman now argued that the transfer was made only by a deed of trust, so he took the matter to court and sued so as to prevent a transfer of the land to the San Miguel Island Company. Waters and the Company argued that it was a complete transfer. In the last line the article included the information that the state also had a claim on the property. The General Land Office was called upon for guidance, and in its correspondence it mentioned no leases and recited that the island was not covered by any land claim. The court ordered the company dissolved and the assets distributed among the stockholders. Apparently this was done, and Waters ended up in sole possession of the business once again.

In 1909, President Taft ordered San Miguel Island to be reserved as a lighthouse reservation. On February 9, 1911, Waters wrote to Taft asking that he revoke the Executive Order and instead allow him to stay on the island. He argued that he had come to California in 1877, bought an interest in San Miguel in 1887, and lived there ever since. He had made many improvements and had been a volunteer weather observer; and, since he was an old soldier having served at the front in the Civil War, it would be an undue hardship at his age to remove his buildings and leave. He had been informed that a lighthouse would be built on this island that he said was only good for sheep. A lighthouse, if any, he wrote, should be constructed on Richardson's Rock seven miles west of San Miguel. He then referred to his bout with the survey team, which had tried to land on the island during President Cleveland's administration. Then he argued anew that he had consulted his attorney and had been advised that no mention was made of the island in the treaty between Spain and Mexico.

A formal brief supplied by attorneys for the Department of Commerce found Water's claim without any foundation whatever. Still, it pointed out, the Department was not under legal obligation to lease the island to the highest bidder or to solicit competitive bids, and a satisfactory disposition of the matter might be to issue Waters a revocable license to use the island for five years. Waters was awarded a five-year lease on November 1, 1911, at $5 a year. In signing the lease, Waters acknowledged ownership by the U.S. Government.

Waters entered into a contract with Robert L. Brooks and J. R. Moore on January 9, 1917. For $30,000, at one-third down, Brooks and Moore received his livestock including some 2,500 sheep and some cattle, improvements including the house and barns, and his lease that was valid until November of 1921. Waters died shortly after on April 26, 1917, after thirty years of "owning" San Miguel Island.

Robert L. Brooks Lease

The entry of Robert Brooks into the San Miguel Island lease opened a new era in the island's history that would last 30 years. Brooks loved the island and the work there, although he lived comfortably on the mainland. He hired men to tend the island sheep ranch, and his employment of Herbert Lester would provide one of the most interesting and well-documented periods in Channel Islands history. The Lester occupation ended suddenly in 1942 and six years later, the sheep ranching period on San Miguel Island came to a close.

Brooks thrived on hard outdoor work where he rubbed elbows with the ranch hands. At the end of the day he loved to drink and talk and spin tales with them, and he kept pictures of himself and these friends. San Miguel Island contributed perhaps half of his annual income, but the island was far more important than income to Brooks. It supplied the romance he needed, a place to talk about, and a place to go and work at shearing time. Shearing time was a huge event, and the whole family got up in the middle of the night to see him off. His shearing hands consisted of several professional shearers and unskilled workers, the latter he referred to as "the bums of Santa Barbara." He cleared the county jail of convicts each year and claimed the city fathers loved him for it. Then he took them out on Joe Castagnola's boat or one of Vail's, and dragged along a barge. The ranch had well-constructed shearing pens, a wool house, and a blacksmith shop. But each year the old wharf had to be torn out and replaced because the waves damaged it badly. New chutes had to be built to bring the sheep down to the wharf where they were loaded on to the barge, 55 at a time, and taken to Port Hueneme, unloaded and transferred to Brooks' ranch at Camarillo. Sheep grazing on San Miguel went well. There were no predators on the island, lambing was considered 100%, and the tax records at Santa Barbara County indicate that none of the unsecured property on San Miguel was ever taxed.

The head count of sheep increased during Brooks' first ten years on the island. By 1921 the island supported more than 4,000 sheep. He sold mutton to the San Antonio Packing Company, R. L. Bliss Packing Company and Hauser Packing Company, and wool to the Standard Felt Company. Not all went well for Brooks. He lost an entire shipment of 50 Shropshire bucks that he had brought to the island. The drought in 1924 caused Brooks to remove all but 500 head from the island, and the following year, in attempting to restock, lost half of the sheep he had imported from Santa Cruz Island to locoweed and lupine. He claimed in a letter to Captain Rhodes of the Lighthouse Bureau that only the native sheep of the island were "enured [sic] to avoid the loco and lupin" and so he had to keep the native ewe lambs to increase the herd rather than selling them. Brooks spent a "considerable" amount of money on Australian Salt Bush seed, which he successfully planted on about 1,500 acres of the island. He wrote that "it started growing in every section of the island where it was sown . . . [it] will grow on the very worst part of the island." Brooks also fenced part of the south side for pasture control, dug a new well and installed a new windmill and piping, and asked for permission to build a new dock. The expenses mounted up, and by 1928, the operation was no longer profitable.

In 1929 Brooks needed long-term help on the island so he called on a friend he had made in the Army and convalesced with at Walter Reed Hospital, Herbert Steever Lester. Lester, an educated and traveled man, suffered from shell shock following the war. Although he was in most ways recovered, he wanted relief from the incessant demands of civilization, and he found ranching on San Miguel completely satisfying.

The Lester Years on San Miguel Island, 1929-1942

Herbert Lester moved to the island in 1929 and in 1930 Lester brought his bride Elizabeth, a librarian from New York, to the island and their legendary lifestyle persisted until his death in 1942. Lester was commissioned as a deputy sheriff and dubbed himself King of San Miguel, occasionally wearing makeshift insignias to carry out the role. Mrs. Lester recorded these years in a book, The Legendary King of San Miguel. Her writing provided a vivid picture of isolation on the island with their two children, made livable through attention to things civilized: building and repair; food preparation for themselves, guests and the shearers; educating the girls; and entertaining the famous and the plain people who came because it was San Miguel Island and because the Lesters themselves attracted them.

Herbert and the new Mrs. Lester arrived on the island in late March 1930, aboard Vail & Vickers (owners of Santa Rosa Island) cattle boat Vaquero that deposited the newlyweds and their things (including her library of 500 books) on the beach. Mrs. Lester soon met the island's Indian sheepherders, Clemente Watchina and Buster, who brought the belongings up to the ranch on a sled while the couple walked. Finding the ranch house outfitted for men (its decorations mainly consisted of arrowheads, fossils and guns), she noted its lack of hot water and determined to make it into a comfortable home. Her addition of books, curtains, pictures helped, and Lester built a fireplace (using bricks from the old ranch house) and installed hot water heaters. The Lesters named it Rancho Rambouillet after the sheep on the island and a favorite place of Herbert's in France.

Mrs. Lester described the house as a "wooden caterpillar," part of a "stockade" closed in by a high fence and a row of utilitarian buildings: a harness room; a blacksmith shop; and an empty structure that Lester eventually remodeled into his famous "Killer Whale Bar" in which he entertained visitors and workers alike. Rain barrels provided part of the water supply. Fleas were rampant. She wrote: "On my first day as an island housewife, I lost no time in getting acquainted with the eccentricities of this historical and fascinating lodge from the notorious trap-door which led from the master bedroom into the gloomy attic which ran the entire length of the house-a matter of one hundred and twenty feet-to the porthole windows-windows which could bear the brunt of the winds. Then the romantic and sheltered cloistered corridor-"monks walk" as John Russell called it, which extended the length of the house on the outside and to which all rooms opened. The front door, which no one ever seemed to use, was a revolving door-one which could survive banks of sand suddenly gusting against it. The quaint dutch door leading from our bedroom, sheltered by a garden, was a romantic thought inspired by a woman, I am sure; a woman who tired of bracing herself every time she opened a window to freshen the air on the opposite side of the house."

The garden consisted of a "straggling arrangement of hardy vines and two fig trees . . . a small sheltered square of wind-free rustic pursuit with some rough, hand-wrought benches and chairs for its furnishings." An attempt at vegetable gardening ended with island birds wreaking havoc. But Mrs. Lester reveled in the island with its "meadows of waist-high grass" and beautiful wildflowers.

Shearing time twice a year brought colorful crews of sheep shearers from the mainland. San Miguel Island was the last stop for the itinerant shearers, who slept and ate in the ranch house and worked hard during their stay. The shearers continued to be issued a ficha for every sheep, although by the Lester era a sheep brought ten cents and a ram twenty-five. Lester partook in the shearing activities, castrating lambs, weighing wool and sewing closed the huge sacks, and cleaning up after all had left. The sheep were put on a small barge from the impromptu pier and shuttled to the Vail & Vickers cattle boat Vaquero for shipment to the mainland.

One seasonal employee, Arno Ducazau, decided to stay and remained with the Lesters until the family left the island: "His days for arduous labor were over, but he chose remote San Miguel and us to a mainland existence for his declining years. This quiet but mirthful old man became my right hand and revered friend in more than one crisis. After our two children came, he was their warden and companion, along with his other responsibilities-all volunteered."

Mrs. Lester traveled to the mainland to give birth to two girls: Marianne Miguel Lester and Elizabeth Edith Lester. She returned after each birth and raised the two on the island. When Marianne reached school age, Mrs. Lester arranged with a teacher friend and the Santa Barbara County schools to teach them on the island, in a tiny schoolhouse made from a playhouse the Vails of Santa Rosa Island had given them. The girls took regular lessons and excelled at their studies. The family exchanged learning opportunities with schools on the mainland, whose pupils would learn about the island and life there and help the girls with their studies about the mainland.

Herbert Lester held a passionate interest in the island's natural and cultural history and made researchers welcome on the island, sharing their knowledge and enthusiasm. Dr. Ralph Hoffman of the Santa Barbara Museum came to the island to study its botany, only to lose his life falling from a cliff east of Cuyler Harbor. Lester erected a wooden cross in Hoffman's honor at what is now referred to as Hoffman Point. Lester happily toured visitors about and made people feel welcome; his wife called him a "one-man Chamber of Commerce."

In 1932 Charles M. Potter landed an airplane in the sheep corral, the first to do so. He told his friend, George Fisk Hammond, about the island and its colorful occupants. Hammond, a young man who loved to fly and could afford the luxury, made more trips to San Miguel than any of the other visitors. He made his first landing in the sheep corral near the ranch house on July 22, 1934. Taking off from his family estate, Bonnymede, along the beach south of Santa Barbara, he could reach the island in less than half an hour.

On Hammond's first visit Lester, who he described as "an astonishingly likable man," greeted him. He shortly began to make regular trips to San Miguel taking groceries, supplies, mail in a special mail pouch and just plain treats the Lesters had been doing without. New friends Hammond and "Herbie" developed a 918-foot landing field east of the ranch complex where they laid out boundary markers, a wind sock and a sign; when the U. S. Coast & Geodetic Survey team came over on December 9, they added it to the official map. Hammond Field appeared on Aeronautical charts until 1965 when its disuse and poor condition prompted the Navy to have it removed from the charts. Lester kept a danger flag ready to fly on the ranch flagstaff if landing conditions were poor. An alternate landing field was found on a 1,500-foot-long dry lake near the west end but it was only available during dry months. Hammond claimed to have landed on many field sites on the island, and once landed on the beach. Between 1934 and the end of 1941, Hammond estimated that he had flown to the island more than 200 times, sometimes more than twice a week.

Despite the luxury of having an impromptu personal pilot, the Lesters still had to be largely self-sufficient. They scoured the beaches for building materials and made do with few extravagances. A two-way radio provided contact with the mainland, over which the Lesters sent official weather reports to Santa Barbara and Los Angeles for the Weather Bureau. The Lesters entertained hundreds of people in the house as their fame grew. Lester kept a guest book in which every visitor signed and left a comment. The family, especially the girls, received letters and gifts from all over the country, and when visiting the mainland would often have news reporters following them.

The national press made much of the Lester years, and stories of San Miguel Island were often printed on the front page. Life magazine called them a "Swiss Family Robinson." On June 23, 1937, the Santa Barbara News-Press carried an article headlined, "Man's Life Saved by Island King." Los Angeles papers followed along with the headline, "Millionaire's Life Saved by Crude Surgery on Island." Robert Brooks had gone to the Island for the annual shearing, and two weeks prior to the news story had been tearing out the landing from which the lambs were loaded for market, preparatory to erecting a new one for the year's shipment. He stood on a slippery rock as he worked, lost his footing, and fell. A rusted bolt extending from one of the piles caught his thigh and tore into his flesh. The wound had to be sterilized and closed or Brooks could have bled to death. Lester had no medical training, but he had army experience and knew the thread he would use had to be strong. Using a curved needle and fish line cleansed in boiling water and Lysol, he stitched the wound closed. There was no anesthetic to ease Brooks' pain, so he simply bore it. Then came the problem of getting Brooks off the island, and since there was no radio, they hoisted the flag upside down to attract a passing ship. None saw the signal. The Vaquero approached two weeks later, four days ahead of its regular schedule. Thanks to Lester's medical care, no infection developed, and when Brooks finally visited a mainland doctor, there was little additional treatment needed. In fact, Brooks told his family that the doctor refused to take any pay as Lester had completed all the treatment necessary.

While the Lesters were in residence on the island, President Franklin D. Roosevelt transferred the control and jurisdiction of San Miguel Island and Prince Island to the Secretary of the Navy for naval purposes on November 7, 1934. The following year Robert Brooks signed a lease with the Navy at $600 a year. The Navy, under pressure for the overgrazing on the island, placed a limit on the number of sheep to be grazed: in 1938, it was 1,200, but it was later reduced to 1,000.

The events surrounding the United States' entry into World War II brought the Lester reign on San Miguel Island to an end, and in a tragic way. Shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Hammond's flights were outlawed, shortages of supplies loomed, and on January 10 the Navy assigned three young enlisted men to act as coastal lookouts. Having no facilities of their own, the men were, in Lester's words, "dumped in our home." The bored young men became a burden on the Lesters, showing no interest in the unique island life and causing small amounts of trouble to the family. Lester became more frustrated with the situation, and one day accidentally chopped off two fingers while cutting wood in anger. Treatments for the wound caused worrisome side effects and Lester became depressed.

On June 18, 1942, a day when the Vaquero would bring Robert Brooks to the island with supplies and mail, Lester wrote a note and left the ranch house. After failing to return Brooks and others searched the island for him. Mrs. Lester found the note, which told her of his intention to commit suicide and where to find his body.

The family's twelve enjoyable and fulfilling years on San Miguel Island came to an abrupt close. The two girls were taken off the island that day, and Herbert Lester was buried in his favorite island spot according to his wishes. A newspaper reporter wrote, "What led him to end his life is as mysterious as the force that impelled him to go to the island originally."

Mrs. Lester remained for two weeks packing up their belongings and saying goodbye to her once-happy home. On July 4, 1942, a Coast Guard boat took her to the mainland where she found a job and a house. She did not visit the island again, but her daughter Betsy has made a habit of visiting and sharing her memories of growing up on the island; Betsy, along with Marianne's grown daughters Jennifer and Barbara Stafford, brought her mother's ashes to the island to lay them next to Herbert Lester in 1981. Mrs. Lester closed her book with this thought about Herbert: "He created a life and a world for himself, and for us on San Miguel. It is all buried, as he is buried, out there, but not alone. Now that I am an old woman, I am glad I had the privilege of sharing it all-for in his imagination we dwelt on our island paradise, the King, the Queen and the two little Princesses. We are still there in spirit, for those who seek us-those who have the skill to dream of what it must have been."

The End of Island Ranching

In 1948 the Navy revoked its lease and ordered Brooks to remove his sheep and other property off the island so that guided missile and bomb targets could be placed on San Miguel. Brooks had 72 hours to accomplish this. He hauled in camping supplies by plane and set up camp for a party of men who covered the island by foot or by horseback looking for sheep in the rugged barrancas. The men drove the sheep down to the Cuyler Harbor dock and into the barge. Some furniture was moved out of the ranch house, but the time was too short. Brooks had to leave over 500 sheep and four horses behind.

In June 1950, he got permission to return and remove his stock. The Los Angeles Times joked that "mutton and munitions don't mix," as their reporter described how four men and four horses were working against a deadline to herd "the unshorn critters through the rugged barrancas of the mist-muddied terrain into corrals and onto barges headed for the mainland." Their first task involved herding the four now-wild horses to participate in the roundup; this took three days. The four herded about 100 sheep at a time, the animals moving slowly because of their heavy coats of wool. Every other day they had enough sheep collected to ship them off by barge, destined for Stearns Wharf at Santa Barbara and markets at Oxnard. But again in the time allotted, every sheep could not be rounded up and the renegades would graze the island unattended for another eighteen years.

The 1960s finally brought an end to sheep grazing on San Miguel Island. Grazing had been much restricted since 1948 when Brooks removed most of his flock, but the restrictions were too late. Once the sheep had removed the protective ground cover, San Miguel suffered severe wind and water erosion. The verdure, trees, and brush hinted at by Cabrillo's log on the islands were gone, but by 1967 some recovery had taken place, a result of the 1948 and 1950 sheep removals.

However, a breeding nucleus remained. In June 1966 the Director of the National Park Service sent the Navy Department "A Suggested Plan for the Management and Protection of Values of San Miguel Island." The report stated that the most pressing need was total elimination of the sheep. The Navy responded with an all out effort from July 17-20 to do away with all of the sheep. Research Biologist James K. Baker of Joshua Tree National Monument flew over the island with a ranger and Navy personnel who hunted down the sheep. By the last day 148 sheep had been sighted through aerial search at near ground level up and down canyons and by criss-crossing the Island from one end to the other. All were disposed of bringing to an end 117 years or more of continuous sheep grazing on San Miguel Island.

In November of 1967, the Lester ranch house burned. Reportedly a Navy aircraft dropped a flare to warn off unauthorized visitors during hazardous naval operations and inadvertently set off the fire. Island ranger Reed McCluskey reported on a conversation with Robert Fromfield and a Mr. Moore in 1983 where the men claimed that they had been regularly trespassing in their planes during the 1960s and 1970s (eventually being convicted for trespass). According to the men, they had landed on the island only to be ordered to leave by a Navy plane that dropped a wooden box, which hissed and emitted smoke. The flare started a fire, which the men on the ground put out. They moved to another part of the island, near the ranch house, where the Navy dropped another warning flare. This also started a fire that the trespassers were unable to extinguish. They fled in their plane as the ranch house, barns and grassland burned.

While the sheep ranching industries on San Miguel Island held no local or state economic significance, its legacy was in the lives of the families that pursued them under great hardship. While little detail is known of Nidever's activities on the island, the fact that he chose such an endeavor while enjoying the life of a prominent pioneer in the comfort of Santa Barbara is of interest. The Waters era on the island makes for some good stories, and yet its significance is not great; Waters and his companions were typical of settlers throughout the west, yet with an island-bound twist that cannot be duplicated elsewhere. Herbert Lester personified the rugged individualism made so popular in the pages of Life magazine, and contributed to the culture of the west in his exploits, which could be called heroic in that he chose to bring a family into the harsh realities, and so the dangers, of survival on a weather-beaten and most isolated island. While few physical resources remain from the ranching period, the life stories of the occupants provide historic significance to San Miguel Island.

Is there something we missed for this itinerary?

Itineraries across USA